Low Back Pain and Pelvic Girdle Pain in Pregnancy

What is already known?

- Approximately 50% of women experience low back or pelvic girdle pain during pregnancy; 25% continue to experience pain 1 year after delivery.

- Pelvic girdle pain is associated with a decrease in regular physical activity during pregnancy.

What are the new findings?

- Being physically active during pregnancy did not reduce the odds of developing low back, pelvic or lumbopelvic pain either during pregnancy or in the postpartum period.

- Physical activity performed in various formats during pregnancy decreased the severity of low back, pelvic and lumbopelvic pain during pregnancy and the early postpartum period.

Introduction

Approximately 50% of women experience low back (LBP) or pelvic girdle (PGP) pain during pregnancy; 25% continue to experience pain 1 year after delivery. A 10 year follow-up study reported that 1 in 10 women with PGP in pregnancy has severe consequences up to 11 years postpartum. 1–5 LBP is pain or discomfort located between the 12th rib and the gluteal fold, and PGP has been defined as ‘pain experienced between the posterior iliac crest and the gluteal fold, particularly in the vicinity of the sacroiliac joints. Despite the fact that both conditions are considered distinct entities, the concomitance of LBP and PGP, herein referred to as lumbopelvic pain (LBPP), puts a greater burden on pregnant women regarding health quality and daily functioning. With repercussions such as disruption of sleep, social and sexual life, work capacity and increased psychological stress, it is not surprising that pregnant women experiencing PGP have also been reported to be less likely to exercise regularly during pregnancy.

In the general population, ‘moderate’ quality evidence suggests exercise has a small positive effect on the severity of LBP compared with usual care, which is comparable with the effectiveness of other non-pharmacological approaches recommended for the management of acute or chronic LBP. However, compared with other cost effective non-pharmacological treatments, such as interdisciplinary rehabilitation, acupuncture, spinal manipulation or cognitive behavioural therapy, exercise is easily accessible as part of a self-management strategy, can require minimal equipment and can be performed at home.

Previous national and international guidelines for exercise during pregnancy endorsed the benefits of exercise during pregnancy in term of fitness, overall wellbeing and decreased risk of developing pregnancy related complications.

Clinically Relevant Anatomy

The lumbar region is constituted of five unique vertebrae that are designed to withstand increased weight and retain a lordotic curve. The vertebral canal of the lumbar region houses the tail end of the spinal cord and the cauda equina.

To maintain stability and provide support, the lumbar region is connected and held secure by an intricate web of ligaments: ligamentum longitudinale anterior and superior, ligamentum flava, ligamentum interspinata, ligamentum intertransversarium and the ligamentum supraspinale. All the mentioned ligaments will provide stability, whereas the longitudinal ligament will also be attached to the intervertebral disc in order to keep the discs in position. Additionally, the lumbar region is supported by strong low back muscles, pelvic muscles and abdominal muscles.

Mechanical

There are several possible mechanisms of injury which could be causing pregnancy related LBP. During pregnancy, changes occur in the facet joints, in the back muscles, and in ligaments. This is mainly caused by the increased release of the hormone relaxin, which causes ligament laxity, and therefore can affect the stability of the spine and lead to back pain.

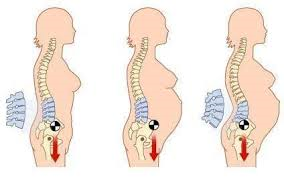

During pregnancy, the enlarging gravid uterus changes the load and body mechanics. Its shifts the centre of gravity forwards, increasing the stress on the lower back. Postural changes can be used to balance the anterior shift possibly causing an extra lordosis. This increases the natural inward curvature of the spine, which increases the mechanical strain on the lower back. It also puts an extra stress on the intervertebral disc, possibly causing a decreased height an overall compression of the spine.

Another contributor is the increase in weight that comes with pregnancy. On average, about 11-15 kilograms are gained during pregnancy. The weight gain increases the amount of force placed across joints, changes the center of gravity, and forces the patient into an anterior pelvic tilt. The anterior displacement of the center of gravity will cause women to shift their heads and upper body posteriorly over the pelvis, causing hyperlordosis of the lumbar spine. This in turn, places additional stress on the intervertebral discs, ligaments, and facet joints and can lead to joint inflammation. In addition, abdominal muscles are stretched and weakened, and the added weight can compress on the lumbosacral plexus.

The abdominal muscles also stretch to accommodate the expanding uterus. As they stretch, the muscles become tired and lose their ability to maintain normal body posture, causing the lower back to support the majority of the increased weight of the torso.

Circulatory

The expanding uterus can press on the vena cava, particularly at night when the

patient is lying down. The pain is possibly severe enough to wake the patient

up. This combined with the increased fluid volume from fluid retention during

pregnancy leads to venous congestion and hypoxia in the pelvic and lumbar

spine.

Psychosocial Factors

Psychosocial factors can also increase low back pain. Pain-related

catastrophizing, depression, pain intensity and time result in an increases in

pain interference. The findings support the potential utility of the

biopsychosocial model. Pain catastrophizing can be considered as a risk factor

in the third trimester of pregnancy.

Risk Factors

Several factors have been associated with the development of low back pain during pregnancy. More specifically, laborious work, a history of low back pain before pregnancy, and a previous history of pregnancy-related low back pain have been identified as risk factors for the development of pregnancy-related low back pain. Pain syndromes during pregnancy impact the abdominopelvic musculoskeletal system, thereby causing abnormal strain on the axial low back elements.

|

RISK FACTORS |

NO RISK FACTORS |

|

LBP history |

Age |

|

Multiple abortions |

Fetal weight |

|

Smoking |

Oral contracptives |

|

Pain during previous pregnancy |

|

|

Number of pregnancies |

Number of pregnancies |

|

History of hypermobility |

|

|

Period of amenorrhea |

|

|

Increased physical workload |

|

|

High body mass index |

High body mass index |

|

Lack of exercise/sedentary lifestyle |

|

|

Pain catastrophizing |

|

There is relative agreement in literature that excessive body weight may be a risk factor for LBP during pregnancy however, there are studies claiming that being overweight is not a risk. The same goes for number of pregnancies before the current one.

Clinical Presentation

Onset

The most common onset tends to be during the fifth and sixth month of

pregnancy, and the pain is usually worse in the evening. Often, the onset of

pain occurs around the 18th week and reaches peak intensity between the 24th

and 36th week of pregnancy. The pain can spontaneously disappear within 3

months, but 7-8% of the patients have a persisting, chronic pain. However it

may start as early as the first trimester or be delayed as late 3 weeks after

delivery.

About 67% of women experience pain at night. Factors that aggravate the pain include: standing, sitting, coughing or sneezing, walking, and straining during a bowel movement. However pain and a disability of the lumbopelvic region are usually proven to be experienced as mild to moderate, except for a minor part (20%) of the pregnant women that will describe the pain as severe.

Area and Quality of Pain

The localization of pain is deep. It’s even possible that

localization of the pain changes over time. Pelvic girdle pain has been described

as “stabbing’’ , pain in the lower back as a “dull ache’’ and the pain in the

thoracic spine is rather “burning’’. Other pain-descriptions are: shooting

pain, feeling of oppression and a sharp twinge.

Pregnancy-related low back pain is characterized by a dull pain and is

more pronounced in forward flexion with associated restriction in spine

movement and palpation of the erector spinae muscles exacerbates pain.

Differential Diagnosis

Some other diagnoses that can be commonly mistaken for pregnancy related low back pain are: Sciatica, Meralgia Paresthetica, thoracic/rib pain, hip pain, coccygodynia, spontaneous abortions, osteomyelitis, osteoarthritis of spine or hip, Cauda Equina Syndrome, Osteitis Condensans Ilii, metastatic cancers, and Diastasis Rectus Abdominis. Other more common differential diagnoses are: disc disease, facet joint involvement and sacroiliac joint involvement. It is important to be able to recognize the subtle differences and differentiate between the comorbidities.

- Disc Disease - Morning pain and stiffness, pain when weight bearing, pain with increased abdominal pressure, history of repeated micro trauma, pain when going uphill, pain with prolonged sitting, pain with sit to stand activity. Sleep is usually undisturbed, pain eases as day progresses and then gets worse again, movement eases pain but not for long (e.g. fidgets).”

- Facet Joint Involvement - Non weight bearing pain, pain with related to movement (specifically rotation), pain increased by lateral compression, history of minor injury, pain is not usually referred to an extremity, pain eases with rest, not affected by coughing or sneezing”

- Sacroiliac Involvement - Pain is usually unilateral and does not midline, can refer to lower extremities, turning while in supine provokes pain, getting out of the car provokes pain, pain is referred to the groin or genitals, pain is related to menstruation prior to pregnancy because of the effects of cyclic hormones on pre-pregnant SIJ ligaments.”

It is also important to differentiate between pregnancy-related low back pain (PLBP) and pregnancy-related pelvic girdle pain (PPGP), as the management and prognosis of the two conditions may differ. Useful methods of differentiation include the site of pain, its character and severity, provoking factors, resultant disability, and the pain provocation tests. Recommended provocation tests are the posterior pelvic pain provocation test, Patrick’s Faber test, and the long dorsal sacroiliac ligament test. In PPGP, the pain is typically concentrated under the posterior superior iliac spine, in the gluteal area, the posterior thigh, and the groin, meanwhile patients with PLBP show the pain to be concentrated in the lumbar region above the sacrum.

Diagnostic Procedures

In order to formulate the correct diagnosis, the patient should be questioned about her past medical history. It is important to concentrate on experienced symptoms, limitations in activities, and movement possibilities. Questions about past pregnancies such as – "Have you experienced any complications with prior pregnancy/ies?" are appropriate. This will help the therapist understand the patient’s health problems and needs. Knowledge of the anatomical and functional disorders, activity limitations and restriction of participation will help the therapist determine her/his role and the need for appropriate interventions. It is important to recognize red flag complaints and contact a doctor to seek further investigation, if they are present.

It is important at the time of initial assessment to differentiate between the lumbar spine and pelvic dysfunction. This can be done during the subjective by inquiring about aggravating factors. Activities such as turning in bed, getting out of a car, walking and climbing stairs may indicate that the origin of pain may be due to pelvic dysfunction. This can then be confirmed with a range of tests for assessing the sacroiliac joint and pubic symphysis.

Outcome Measures

Several validated instruments to assess back pain exist for general population who can be used in the diagnosis to estimate the complaints more objectively:

- Visual Analogue Scale (VAS)

- Roland Disability Questionnaire (RDQ)

- Québec Pain disability index (QPDI)

- PHotograph series Of Daily Activities (PHODA)

- Impact on Participation and Autonomy (IPA)

- Pain Behavior Scale (PBS)

- Oswestry Disability Index.

Examination

During an examination of a pregnant patient, positioning is a key consideration. Excessive time in supine is not recommended due to the weight of the uterus on the vena cava and vital structures. Based on the level of pain and disability of the patient, and potentially the size of the pregnant abdomen, certain tests and measures may need to be modified for this population. Excessive time in supine is not recommended due to the weight of the uterus on the vena cava and vital structures.

Physical Exam

Examination should include observation of the posture and gait, neurologic

screen to rule out underlying pathology, range of motion, muscle tests,

palpation, muscle length tests, and assessment of joint mobility.

The Active Straight Leg Raise test can prove that patients suffering from LBP use significantly more muscle activity, but produce less force, compared to the healthy groups. Healthy controls achieve more hip flexion force at both 0 and 20 cm than PLBP. It’s important to distinguish posterior pelvic pain from low back pain during physical examination. Recommended provocation tests are the Posterior Pelvic Pain Provocation (PPPP) test, FABER test, long dorsal sacroiliac ligament test and standing on one leg. As mentioned above, the pain is typically concentrated under the posterior superior iliac spine, in the gluteal area, the posterior thigh and the groin in case of PPGP. Patients with PLBP show pain concentrated in the lumbar region above the sacrum. Palpation over soft tissue of the sacroiliac, pubic symphysis, and gluteal regions can also distinguish pelvic pain from tenderness over the back above the waist. Studies show that both methods are effective although pain provocation tests are more reliable than palpation tests.

The Trendelenberg sign examine the ability of the lower back, pelvis and hip to transfer load unilaterally in a weight-bearing position. The test occurs positive when the patient drops the pelvis on the non-stance side. In this case the patient has weakness of the abductor muscles. The following findings are commonly revealed: Paravertebral muscles are tender to palpation, back muscles weakness, decreased ROM in flexion. The description of the pain is often not localized and may be intermittent. It is possible for the pain to radiate down as far as the calf.

Modified Tests

Some tests cannot be performed as per usual given the patient's growing abdomen therefore the following modifications are needed.

Walk B. Texas State University's

Evidence-based Practice project.

Walk B. Texas State University's

Evidence-based Practice project.

Hip Flexor Length: To modify the test position of the ‘Thomas Test’ the patient will have to sit on the edge of a table or mat, and extend the test leg as much as possible, while maintaining slight knee flexion. The pelvis should be kept in a neutral alignment. A patient with non-impaired flexibility should be able to extend her hip perpendicular to the floor.

SI Joint Examination: If the patient is unable to stand, instruct the patient to lie in supine and perform a pelvic bridge. The bridge will place the pelvis in neutral - the ASIS’ can be palpated for symmetry.

Physical Therapy Management

When treatment is necessary for low back pain, conservative management is the ideal option. Treatment starts with education and activity adjustments. Educational strategies focus on back care measures, such as ergonomics, which teaches women correct posture; pregnant women learn how to stand, walk, or bend properly, without causing stress on the spine. Accurate posture is essential to improve low back pain. Braces that ensure correct body posture are also available if the instructions are not enough. In regard to activity modifications, scheduled rest during the day is helpful for relieving muscle spasms and acute pain. During this time, posture is again important as both feet should be elevated, which will help flex the hips and decrease the lumbar lordosis of the spine. (Level of evidence: 2A) (Level of evidence: 4)

Studies have found that pregnant women with low back pain, who participate in both education and physical therapy, have less pain and disability, higher quality of life, and improvement on physical tests. Physical therapy encompasses several factors such as postural modifications, back strengthening, stretching, and self-mobilization techniques. Functional stability can be maintained throughout pregnancy by strengthening the muscles around the lumbar spine through various back exercises. (Level of evidence: 2A).

Treatment depends on the diagnosis and timing of pregnancy (before or after childbirth). The patient should understand her own symptoms and be motivated to remain active.

Red Flags

The following are crucial to identify during treatments: (Level of evidence: 2 A)

- Vaginal bleeding

- Dizziness/feeling faint

- Shortness of breath

- Chest pain

- Headache

- Muscles weakness

- Calf pain or swelling

- Uterine contractions

- Decreased fetal movement

- Vaginal fluid leakage

- Neurological symptoms

Physical Therapy Goals

The focus of physiotherapy is to: (Level of evidence: 1 A)

- Restore biomechanics during daily activities

- Improve lumbo-pelvic stabilization

- Educate and prevent

What To Expect on Your First Visit?

Your first session with a physiotherapist will include a detailed assessment of your condition, beginning with questions about your symptoms and general medical history. You can rest assured that everything you tell the physiotherapist will remain completely confidential.

The assessment will be followed by a physical examination. The type of examination carried out will depend on the condition you are attending to and may include an assessment of posture and function, muscle tone, flexibility, and strength.

What Are The Treatment?

Based on the results of the assessment, your physiotherapist will recommend a treatment program that has been specifically developed for you.

Treatment May Include:

- Manual therapy

- Exercises to strengthen weak muscles

- Stretches to reduce tension in tight muscles

- Kinisio-taping therapy

- Acupuncture

- Advice regarding activities

- Discussion surrounding possible lifestyle changes that will help manage the problem

- Provision of supports/braces

In line with the ICF model approach, our experts will devise your treatment program. They will use a combination of pelvic floor exercises, pilates and/or electrical stimulation, advice on sleeping postures, toileting and positional modifications, relaxation techniques for treating your condition.

Kindly contact us to discuss your options with our physiotherapists.

References:

- https://bjsm.bmj.com/content/53/2/90

- https://www.physio-pedia.com/Low_Back_Pain_and_Pregnancy

- https://www.physio-pedia.com/Pregnancy_Related_Pelvic_Pain