Sitting Disease and Ergonomics. The Impact on Low Back Pain

There is a growing set of evidence that links daily sitting time and chronic diseases diabetes and heart disease. Many don’t realize how much time is spent sitting down, especially since most tasks that once required us to be on the move (paying bills, shopping, etc.) have become unnecessary. In fact, the average person who sleeps 8 hours a day can expect to spend the remaining 16 hours performing work or household-related tasks. Many public health experts, including the U.S. National Institute of Health have spent quite a bit of time researching the effects of an overly sedentary lifestyle, which can lead to a variety of health factors like heart disease, cancer and obesity. However, many still don’t know what sitting disease actually is.

What Exactly Is Sitting Disease?

Sitting Disease is a term used by medical professionals to describe metabolic syndrome and the factors that encourage sedentary behaviors. It’s interesting to note that research and studies related to sitting disease didn’t have a term until 2004, when medical researchers decided to use “inactivity physiology” to describe “the potential causal role of sedentary behaviors in the development of cardiovascular and metabolic disease”. The NIH has also found that in studies related to inactivity physiology, it is highly likely that sitting disease will become a more serious health problem with further innovations in technology and culture. The Centers for Disease Control has also conducted some studies specific to the effects of prolonged sitting in the workplace. They have found that performing a physical activity to disrupt sedentary behaviors related to sitting disease does help to decrease the development of metabolic syndrome, but at a very slow rate. Why does it matter so much? A recent study suggests that as your sitting time increases in frequency and duration, so does your risk of early death. According to juststand.org, sitting disease is by far one of the most unanticipated health threats of our time. It isn’t hard to see why, since most don’t believe that sitting down, which is considered a form of rest and relaxation, can also lead to serious health factors overtime.

A survey of Australian males aged over 45 found that those who spent more than 4 hours a day sitting were significantly more likely to be suffering from a chronic disease.

Management

- Reduce the total time spent sitting a day.

- Take regular breaks from sitting.

Suggested Approaches For Office Workers To Reduce And Break Sitting Periods:

- Use a standing desk.

- Use standing meetings.

- Take telephone calls standing.

- Walk to see a colleague rather than call or email.

- Eat lunch away from your desk.

Ergonomics

Often referred to as "human factors", ergonomics is the science of applying physical and psychological principles within an environment to increase both productivity and well-being.

The study of ergonomics can be divided into three main areas of research:

- Physical ergonomics

- Cognitive ergonomics

- Organizational ergonomics

Physical ergonomics places a greater emphasis on the human anatomy, physiology, and bio-mechanical factors influencing movement patterns and posture. This area of ergonomics is therefore of significant interest to physiotherapists and one in which we regularly address due to having a rich, in-depth understanding and knowledge of these factors.

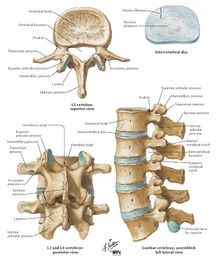

Clinical Anatomy of Lower Back

The lumbar spine - This is where most back pain occurs, in and around the five vertebrae (numbered L1-L5). In between each vertebra, there is an intervertebral disc. This is known as the intervertebral disc joint. There are also two (left and right) facet joints between each vertebra. L5 is also attached to the sacrum. The sacrum then attaches to the pelvis, creating the sacroiliac joint.

The Vertebra

Each vertebra consists of many features,

including a vertebral body, a spinous process, the spinal canal for the spinal

cord, and transverse processes. There are several distinct features of the typical lumbar vertebra. These include:

Each vertebra consists of many features,

including a vertebral body, a spinous process, the spinal canal for the spinal

cord, and transverse processes. There are several distinct features of the typical lumbar vertebra. These include:

- Large vertebral body

- Short and thick spinous process

- Relatively vertical facet joint

- A mammillary process on the posterior aspect of the superior articular process

- L5 has the largest body and transverse process of all vertebra

Structural Function

The main function of the lumbar spine is to bear the weight of the body. It absorbs the stresses of lifting and carrying objects as well as general movement.

Below discusses the structural function of the spine:

- The spine holds an increasing amount of weight as you move down into the lumbar region, for this reason, the lumbar vertebra has the larger bodies in the spine.

- Due to the relative size of the spinous process and body, the lumbar spine has the largest degree of extension.

- The lumbar spine allows flexion, extension, and lateral flexion but not rotation and this is due to the orientation of the facet joints

- The mammillary processes provide an attachment point for many lower back muscles.

The Intervertebral Disc

Between each vertebra, there is an intervertebral disc. The intervertebral disc is made out of the nucleus pulposus, annulus fibrosis, and the cartilage endplates.

- Nucleus Pulposus: This is a highly hydrophilic substance that is located in the centre of the intervertebral disc. It acts as a shock absorber as it allows for the distribution of pressure in all directions.

- Annulus fibrosis: This contains multiple fibrocartilaginous bands. It surrounds the nucleus pulposus and its main function is to protect the nucleus pulposus.

- Cartilage Endplates: This is found on the superior and inferior ends of the disc and represents the anatomic limit of the disc. Its main functions include protecting the contents of the disc and providing a source of nutrition to the disc.

Ligaments

The main ligaments of the lumbar spine include:

- Anterior longitudinal ligament: This is a thick band of tissue that runs along the anterior surfaces of the vertebral bodies. It protects against hyperextension of the spine.

- Posterior longitudinal ligament: This is thinner than its anterior counterpart and runs along the anterior wall of the vertebral canal. It is involved in preventing disc prolapse.

- Interspinous ligaments: This connects consecutive spinous processes together within the spine. It mainly limits the flexion of the spine.

- Ligamentum flavum: This runs between each consecutive laminae and is extremely elastic. Its function is to help maintain an upright posture and to resume this position after flexion. It also prevents buckling of the ligament during extension.

- Supraspinous ligament: Connects the ends of each spinous process together. Helps to prevent hyperflexion.

- Iliolumbar ligaments: This consists of two parts, an anterior and posterior part. It plays a huge role in the stability and restricts both side flexion and rotational movement at the lumbosacral junction.

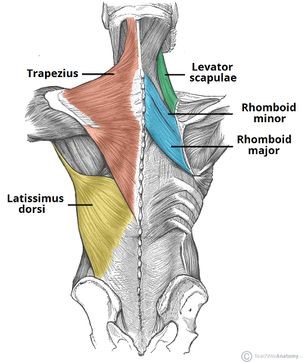

Muscles of the Trunk

Superficial muscles of the back

There are multiple muscle groups that support the spine. Each plays an important role in stabilising the trunk and allowing movement into flexion, extension and rotation.

Muscles that attach into the lumbar vertebrae:

- Erector spinae

- Interspinales

- Intertransversarii

- Latissimus dorsi

- Rotatores

- Serratus posterior inferior

The lumbar spine is also supported by the muscles of the abdomen and pelvic floor.

Effect of Sitting on our Body

There are many studies that look into how sitting affects our spine, some of these even look into how we change physiologically.

One study found that when flexing the spine, to flatten the lumbar spine, improves the transport of metabolites in the intervertebral discs, reduces the stresses on the facet joints and gives the spine a high compressive strength. This suggests very positive effects of flexing the spine, however, this study did also report negative effects including increasing stress on the annulus fibrosis and increasing the hydrostatic pressure in the nucleus pulposus.

Further studies have found that sitting in a flexed position also reduces the activity of abdominal muscles which play a key role in stabilizing the back

Finally, a recent study found that when a person sat for prolonged periods of time (for 4 hours), there was a significant reduction to the height of L4-5 intervertebral disc, however, the sample size had a female predominance and studies have found that males and females do respond to static lumbar flexion differently and therefore this may not be generalized to the population as a whole

Low Back Pain

Low back pain can be defined as pain originating in the low back region that may or may not radiate down into the legs. This pain can further be categorized by sensation such as dull or sharp pain as well as duration:

- Acute ( <6 weeks )

- Sub-acute ( 6-12 weeks )

- Chronic ( >12 weeks )

Low back pain may be further classified by the underlying cause as either mechanical, non-mechanical, or referred pain. The symptoms of low back pain usually improve within a few weeks from the time they start, with 40–90% of people completely better by six weeks.

Sitting and Low Back Pain

Occupational low back pain is one of the most prevalent types of back pain. Multiple factors can be responsible (e.g. heavy lifting and poor manual handling) putting multiple professions at risk. Study reveals that those working in an office job, 90% report experiencing musculoskeletal pain (predominantly reported as low back pain).

The main causes for this sitting induced back pain have been identified as:

- Sustained sitting

- Increased activation of the spinal muscles due to specific sitting postures

- Lack of variation of movement

What Is a Good Sitting Posture?

From research it seems that protecting our lower back when sitting is multifactorial. These factors are; the environment, time and posture and all influence lower back pain when we sit.

One study found that adapting our environment is important for low back pain. This includes making sure our eyes are in line with monitors, our devices such as keyboards are close and our chairs are a good height. The length of time we sit may also have an impact on lower back pain.

Recent evidence has proven that sitting time is positively associated with LBP intensity. This study looked at 201 blue-collar workers and the length of time they sat in both their day job and leisure time and found that those who sat for longer throughout the day had a higher prevalence of low back pain. However, this study used a cross-sectional study design and therefore a causal relationship cannot be made. One paper recommends moving every 20 minutes in order to reduce the likelihood of lower back pain caused by sitting.

A further study found that sitting for more than half a workday and sitting in an “awkward posture” significantly increased the likelihood of LBP. This shows that posture does impact back pain, but usually when maintained for a long period. A study found that people who sat in a flexed, more relaxed position for long periods of time did experience more back pain than those who did not.

Due to all of this evidence, it is important for us as Physiotherapists to consider all of these factors when helping someone with sitting induced LBP. It could be argued that there is no one answer to “what is good sitting posture” and that as long as we keep moving, make sure our environment is adequate and keep a natural posture, we can say that we are maintaining a good sitting posture.

Prevention and Rehabilitation of Sitting Induced Low Back Pain

As with most incidences of low back pain there are multiple approaches that Physiotherapists can take in order to help manage symptoms and prevent re-occurrence. The four main areas explored in the literature for the management of low back pain induced by sitting are as follows:

- Education around postural awareness

- Discouraging long sedentary periods.

- Prescribing exercises to improve postural control.

- Recommending equipment that will support a neutral spine.

Ergonomics Education

The goal of the ergonomics program is to provide an efficient and safe work environment for all employees, including through education and prevention programs. Ergonomists regularly present at department and staff meetings of all sizes to share information on ergonomics evaluation and resources, implementing stretching programs, and other safety-related topics. Presentations can vary in length to fit your needs.

Maximum human performance is achieved at the intersection of good workplace design and a healthy, fit and engaged workforce.

An ergonomically efficient workstation with an unhealthy and unmotivated worker using poor work practices is not your goal. A healthy, motivated worker that is forced to work outside her body’s capabilities and limitations is not your goal. Your goal has to be a well-designed and efficient workstation within the capabilities and limitations of a healthy, fit and engaged worker.

So ergonomics education should focus on a process to improve workplace design (the ergonomics improvement process) and a healthy, fit and engaged workforce. Your education and training content should reflect these two fundamental needs of a process to improve human performance. You will need ergonomics training content for an effective ergonomics improvement process and you will need MSD prevention and wellness training content for a healthy, fit and engaged workforce. To achieve maximum human performance at your facility, you will need an effective ergonomics improvement process and a strategy to improve employee health, fitness and engagement.

One study found that improvements in postural awareness were longitudinally associated with reduced pain in patients with spinal pain and this really highlights the importance of educating our patients.

Finally, one study educated office workers about ergonomics and found a significant change in perception of health and reported less pain and discomfort at work when sitting.

Movement for Prevention and Rehabilitation of Sitting Related Low Back Pain

Various interventions are used across the spectrum of occupational settings in an attempt to both minimize the risk of low back pain arising but also reduce the impact of sitting on those with already existent low back pain. However, the utility and effectiveness of these interventions is somewhat mixed within the literature. The main source of evidence regarding these interventions comes in the form of a Cochrane systematic review by Parry et al. (2019) who, after exploring research surrounding the use of such interventions as sit-stand workstations, treadmill workstations, and activity trackers, found the effectiveness of these interventions in reducing both the intensity and presence of low back pain for sitting based individuals at work was poor.

Another movement based intervention not included within the Cochrane systematic review involves the use of "dynamic sitting" which involves the use of both active and passive implements to encourage regular movement of the trunk and lower extremities in a seated position. O'Sullivan et al. (2012) investigated the effectiveness of dynamic sitting via a systematic review. They concluded that although the evidence regarding this topic was of high quality, there were inconsistent results to support and recommend the use of said intervention.

The primary movement-based intervention that the literature appears to moderately support is the implementation of movement breaks throughout the day for those individuals who are in a seated position for prolonged periods of time such as office workers. Waongenngarm, Areerak and Janwantanakul (2018) carried out a systematic review evaluating "movement schedules" with work durations ranging from 5 minutes to 2 hours and breaks lasting 20 seconds to 30 minutes. They found low-quality evidence supporting both a reduction in pain and discomfort for those carrying out movement breaks which also include simple changes in postural position with detriment on productivity. This is further supported by a later study by Sheahan, Diesbourg and Fischer (2016) who also found that even short, regular breaks of standing from a seated position reduced both the regularly and intensity of acute low back pain within a office worker population.

Postural Rehabilitation

Postural rehabilitation describes performing

exercises that are specifically focused on increasing core strength and body

alignment in order to improve postural control. Prescribing strength and

flexibility exercises particularly, allows for better control of the lumbar

region during both slow-voluntary and fast-reflexive movements; thus reducing

the likelihood of low back pain.

Postural rehabilitation describes performing

exercises that are specifically focused on increasing core strength and body

alignment in order to improve postural control. Prescribing strength and

flexibility exercises particularly, allows for better control of the lumbar

region during both slow-voluntary and fast-reflexive movements; thus reducing

the likelihood of low back pain.

Several different methods of postural

rehabilitation have been devised, each putting greater emphasis on a different

element of postural control e.g. proprioception, balance and core muscle

strength. However, all have the ultimate aim of preventing and managing low back

pain.

Several different methods of postural

rehabilitation have been devised, each putting greater emphasis on a different

element of postural control e.g. proprioception, balance and core muscle

strength. However, all have the ultimate aim of preventing and managing low back

pain.

The most widely researched

and recommended approaches are Pilates and the McKenzie method. The focus of

Pilates is to encourage postural control through engagement in isometric

contraction of the deep core and pelvic floor muscles; it also puts a strong

emphasis on breathing control during movement. The McKenzie method takes a

slightly different approach, focusing on correcting posture, usually through

the restoration of lumbar lordosis.

The most widely researched

and recommended approaches are Pilates and the McKenzie method. The focus of

Pilates is to encourage postural control through engagement in isometric

contraction of the deep core and pelvic floor muscles; it also puts a strong

emphasis on breathing control during movement. The McKenzie method takes a

slightly different approach, focusing on correcting posture, usually through

the restoration of lumbar lordosis.

In 2019, Paolucci et al conducted a literature review that investigated and compared the effectiveness of these two techniques, alongside three other methods of postural rehabilitation. The review concluded that each approach had sufficient evidence to support its efficacy in reducing back pain and disability, and improving quality of life; for Pilates and the McKenzie method particularly, the corresponding exercises were found to be more effective than alternative pharmacological and instrumental treatments. Though the review did not focus of sitting induced back pain specifically, the principles of the postural rehabilitation techniques included are applicable to our population of interest.

Use of Equipment for Prevention and Management

With back pain being such a common issue the market has been flooded with equipment to try and alleviate back pain or relieve the symptoms. The equipment ranges from exercise balls and back braces to standing desks which are appearing in offices more and more. Research has been carried out on all the equipment to varying degrees. For example there is minimal research on sitting exercise balls rather than chairs and back braces specifically for low back pain rather than post-operative, however, they are used frequently due to them being cheap and easily accessible.

Exercise Ball

One of the most common tools in rehabilitation and exercise is the exercise ball. Their popularity has risen in recent times as they are cheap and easily accessible, claiming not just to combat back pain but also to aid concentration whilst working. Research on its effects on back pain is limited, but generally does not show favourable results.

One of the first studies was conducted by Kingma and Dieën (2008), who investigated static vs. dynamic posture. This was done by comparing females working at computers on an office chair to those on an exercise ball, and measuring muscle activity in the spinal muscles. Sitting on a ball led to 33% more trunk motion and 66% more variation in lumbar muscle activation – however, it also led to more spinal shrinkage. They concluded that whilst the advantages may slightly outweigh the disadvantages, overall, the real term benefits of sitting on an exercise ball were negligible.

In addition to this, Elliot et al. (2016) conducted a study comparing sitting on a ball for 90 minutes per day instead of a chair, to investigate the effects on lower back pain and core muscle endurance. Their results were not statistically significant, and they concluded exercise balls have little-to-no benefit for lower back pain, but did somewhat improve core endurance in the sagittal plane.

Back Support Seat Attachment

A variety of seat attachments exist, for chairs in the office, at home and in the car, which claim to reduce lower back pain. However, the literature is mixed on the effect they have.

One of the earlier studies specifically targeted so-called ‘ergonomic chairs’, which have built-in lumbar support with the intent to improve posture and alleviate back pain, conducted by van Niekerk et al. (2012). Some subjects reported a reduction in back pain after the intervention, however the study reported that they used poor randomization procedures and lacked concealed allocation. This would suggest the chairs were possibly only useful for specific members of the population, and/or the existence of the placebo effect. They further stated being unable to make any strong recommendations due to the amount, level and quality of evidence being insufficient.

Following on from this, Curran et at. (2014) found that the addition of a backrest and seat pan actually increased lower back pain in individuals with extensor-related pain, and generally provided no reduction in lower back pain for the general population. This is also supported by Ortiz et al. (2020), who investigated back supports for prolonged car journeys, and found little benefit.

Back Braces

Evidence surrounding back braces is conflicting and does not form a strong conclusion. For example, when combined with physical therapy and pain medication, some studies suggest increased mobility and pain scores with a back brace compared to without – whilst some studies highlight a concern that back bracing may lead to muscle atrophy (Dang, 2018). Overall, research is very limited, with methods and patient participation being of poor quality, and thus more research needs to be conducted in this area.

Standing Desks

Standing desks for workplaces have grown in popularity in recent times, orbiting the idea that standing and moving are beneficial to reducing back pain. These range in quality, from around $150 to well over $1000, all with the same fundamental idea: to allow you to work in a standing posture when necessary, and being able to adjust back to normal desk height to allow for flexibility.

Claus et al. (2008) conducted a systematic review that suggested standing desks only provided benefits to a specific subgroup of the population – those with degenerated inter vertebral disks. They stated that for a healthy individual, sitting was no worse than standing for the incidence of lower back pain. However, following on from this, Pillastrini et al. (2010) claimed that standing desks reduced both the severity and risk of lower back pain. In a longitudinal study conducted over 30 months, they studied 100 video display terminal workers, following up at 5, 12 and 30 months to question the effects. However, one issue with this study was that it was not solely focused on standing desks, but included other interventions over the course of the 30 months.

As such, overall, more research – and more specific research – would need to be conducted to evaluate the effects of this trend. Research would also have to study the differences in quality between cheaper and more expensive desks, to understand if there was then a difference in outcome.

References:

- https://physio-pedia.com/Sitting_Ergonomics_And_The_Impact_on_Low_Back_Pain

- McKenzie method: https://www.physio-pedia.com/Mckenzie_Method

- https://ergo-plus.com/ergonomics-training-for-human-performance/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Low_back_pain

- George ES, Rosenkranz RR, Kolt GS., Chronic disease and sitting time in middle-aged Australian males: findings from the 45 and Up Study. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2013 Feb 8;10:20. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-10-20.